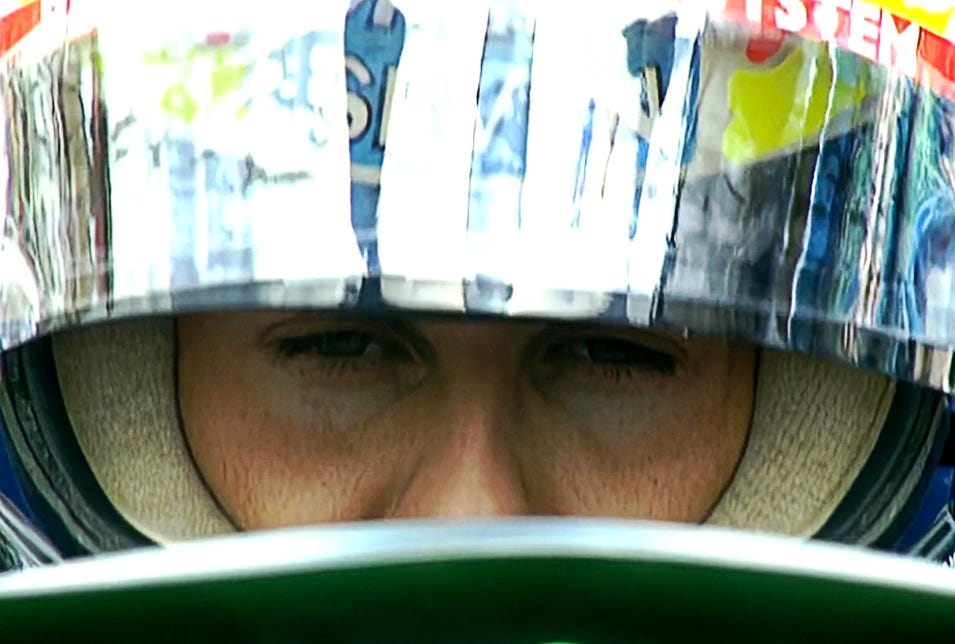

Top Gear: Schumcher's Problem Solving at Barcelona 1994

The German drove 44 laps with the transmission stuck in 5th gear.

Michael Schumacher didn’t enter Formula 1 to finish 2nd. He did it to win. And he was greedy about it. Preferably, he would win every race. Yet on 43 occasions throughout his career, he had to accept a trophy for finishing as the runner-up.

The first time was in Spain, in 1992. After an unusually overcast and rainy race for Barcelona, he stood on the podium one step below Nigel Mansell. Two years later, at the very same Circuit de Catalunya, he had to concede victory to another Williams driver from the British Isles, Damon Hill.

Although the weather was much kinder than it had been two years prior, Schumacher had to cope with a certain discomfort for two-thirds of the race, which made his Sunday more challenging than he had probably anticipated. The discomfort of having only one gear.

That is why this P2 stands out significantly among the other 42. It even surpasses many of his victories, if not all of them.

Nice Bad Beginnings

The German, starting from pole position, maintained his lead after the first two corners. He quickly established a pace that no one could match. Hill appeared smaller and smaller in his mirrors. After 10 laps, Schumacher held an 11.246-second lead, which continued to grow. By lap 18, it had increased to 17.904 seconds, as the German clocked the fastest time of the race at 1:25.155.

As his first pit stop approached, he encountered a gear selection problem. He radioed the issue, and Benetton instructed him to box. The exact moment when the transmission became stuck is difficult to pinpoint, but for sure Schumacher had only one gear as he entered the pit lane at the end of lap 21.

Willem Toet, the Head of Aerodynamics at Benetton at the time, recalled the cause lied in faulty hydraulics:

The team pitted the car a little earlier than they might have (still some fuel in the car) so they could have a quick look. Red oil was visible at the rear of the car. Red oil. That’s hydraulic oil and Benetton were using that to actuate gear changes. The car was stuck in 5th gear. 5th gear. Imagine trying to start from the traffic lights in 5th gear in your road car. Quite a challenge.

Schumacher accepted and rose to the challenge, aided by the “magnificent torque curve” of the Ford V8 Zetec-R engine that powered his car. The 1994 Spanish Grand Prix also stands as a testament to the work of Cosworth engineers and their chief designer, Geoff Goddard.

A Steep Mountain to Climb

The internally damaged Benetton B194 was able to accelerate out of the pits, but it had to circle the track an additional 44 times.

The first one, the out lap, presented a rather depressing prognosis, as Schumacher was 10.768 seconds slower compared to Hill’s out lap. Two backmarkers overtook him as if the roles were reversed, and the German was on the verge of being a lap down. Before he could reach the finish line, McLaren's Mika Hakkinen seized the lead from him. Soon he was passed by Hill.

The situation was dire, but not impossible. Fortunaltely, the transmission got stuck in an “ideal gear.” 6th would’ve been too high for some of the slower corners, while the lower gears would’ve been too sluggish on the straights. 5th was "optimal" for the modified layout of the Barcelona circuit, which included an artificial tire chicane implemented as a safety measure before the Nissan corners—a fast right-left section between today’s Turns 9 and 10.

Steve Matchett, the Benetton mechanic at the time, recalled in an episode of Formula One Decade covering the race in question that the team advised their driver to continue if he could do so safely.

The German only inquired if he needed to stop for fuel again. Yes, was the response.

The Michael

One of the many traits that characterized Schumacher, as well as Ayrton Senna, and which is best epitomized in modern Formula 1 by Max Verstappen, is supreme confidence.

It’s only natural to develop confidence in a field in which one excels. This holds true for driving, cooking, toss juggling—essentially, every skill. When a German boy possesses exceptional talent behind the wheel and stands out among his peers, he is likely to develop an almost irrational level of self-belief. This heightened confidence may make him quite reluctant to give up, even when faced with the challenge of walking a tightrope.

Another component that helped Schumacher succeed was his adaptability and approach to racing. Toet remembered that:

Michael always had a very precise, consistent way of driving; he could adapt his style to suit whatever was necessary. He was also very analytical and extremely serious about his job.

This analytical mindset led to famous experiments with speedometers, which Richard Marshall, the Head of Electronics at Benetton, designed at the driver's request. Three speedometers were placed directly above the steering wheel. The middle one displayed real-time speed, while the left and the right ones, indicated minimum and maximum speeds in corners. Schumacher utilized them to, among other things, optimize his driving style.

Equipped with supreme confidence, adaptability, an analytical approach, and the torque monster engine, he proceeded with the task.

The Adjustment

The biggest challenge lied in the slow corners. Toet explained:

Michael quickly realised that he had “no” power to pull the car out of the slower corners so had to change his racing lines to carry more speed at the apex (slowest point) of the corners - not normally the fastest way in a Formula 1 car.

It took the German some time to find the optimal racing lines. The task began poorly, with a time of 1:31.835 on the 23rd lap. Meanwhile, Pierluigi Martini, driving a backmarker Minardi in P13, set 1:30.453.

Schumacher put his brain to use and, with each completed lap, he kept adjusting and shaving off time.

First, he broke the 1:29 barrier on lap 28 with a time of 1:28.438. He then consistently lapped in the 1:27 range and even clocked times in the 1:26s. On lap 40, he set his best mono-geared time of 1:26.171. Quite an improvement from 1:31.835 at the beginning of the stint. Exactly 5.664 seconds.

Schumacher was no longer walking a tightrope. He was running.

The Battle for P2

Between the 28th and 40th laps, Schumacher, on average, drove only 0.121 seconds slower than Hill, who was leading the race. However, the Williams driver was not pushing himself.

In his first stint, excluding the opening lap, he averaged 1:27.069, while his second stint was 0.476 seconds slower. Furthermore, Hill's best lap from the first stint was 1:25.874, but he did not exceed 1:26.756 in the second stint. He clearly had pace to spare, but there was no reason to push it.

The television feed switched to Schumacher’s onboard camera as soon as they noticed his struggle. It displayed the telemetry data, and the green circle around the number 5 indicated to everyone, including Benetton’s competitors, that the German was limited to just one gear.

Funny thing is, the team sent representatives to the television production team to plead with them to stop.

Obviously, Williams must have picked up on that and given their driver appropriate instructions, as Schumacher wasn’t a threat. Hill also didn’t have to worry about Hakkinen, who was clearly on a three-stop strategy, having pitted very early on lap 15. All the Brit had to do was bring the car home.

It was Benetton and their driver who had to be concerned about Hakkinen. The Finn was the fastest among the top 3. After his second pit stop on the 30th lap, which had dropped him to P3 and left him 10.290 seconds behind Schumacher, he was gaining on the German by 0.294 seconds per lap.

They both boxed for their final refueling and tire change on lap 45. Three rounds later, Hakkinen was only 2.929 seconds behind. With 17 laps remaining, it appeared he would secure P2 with ease.

However, his pace was apparently too much for the Peugeot engine powering his car. It gave up the ghost before Turn 5 on the 49th lap.

This made Schumacher's task significantly easier. He cruised to the finish line and eased off on the final 5 laps.

The Unthinkable

One aspect that has not been mentioned previously, which significantly contributed to completing the task of driving 44 laps with only one gear available, was Schumacher's experience in sports cars. After the race he said:

In the beginning I was doing lap times of 1 m 32s. I found a way to use fifth gear differently which meant I could do 1 m 26s again. It surprised me very much, but with my GpC experience I know a lot of ways of running differently, of saving fuel and changing my style of driving. It was this style of driving which helped me very much today. It got me out of the worst trouble.

Speaking about fuel conservation, Matchett noted that the team analyzed the telemetry after the race and confirmed that fuel consumption improved as a result of Schumacher adjusting his driving style.

Pretty impressive: the efficiency and the drive, of course.

So impressive that it seemed too good to be true. Matchett mentioned that some journalist didn’t buy it any one bit, until the team released the telemetry.

After the race, McLaren conducted a simulation. The result gave a thumbs up to Schumacher. According to it, “it was possible, and if you adjusted your style you could get by without losing more than a couple of seconds a lap.”

Peak Schumacherness

It is undoubtedly one of Schumacher's best drives. Not because of the end result. Frankly the finishing position is not that relevant. It would’ve been no less impressive if he had reached the chequered flag 4th or 5th.

Although the podium was a great reward for his effort and tenacity. For his ability to adapt on the fly. For finding a suitable solution to a difficult problem in a high stress situation. For systematically improving his pace and setting competitive times. All of this while dealing with an issue that, at first glance, should've led to his retirement.

Problem solving for the ages.