Think on Your Feet and Run Like Hell: Schumacher's First Victory

One year after his debut Michael Schumacher returned to Spa-Francorchamps to take his maiden win.

(WARNING: It’s a rather long read. If you want to skip the backstory and go straight to the race, scroll to The Ardennes Roulette.)

The name Schumacher is inextricably linked to the Spa-Francorchamps circuit. There, he achieved some of his greatest victories, there he tasted bitter disappointment, there he clinched his last championship… And, first and foremost, there he made his debut in Formula 1. To make it happen, his manager, Willy Weber, even lied that his client had raced there many times. Schumacher had never seen the track. However, once he saw it, he fell in love:

Spa-Francorchamps is simply one of the last 'old' tracks. There aren't too many of them left. You drive a track like that with a very special feeling.

To take these curves, Eau Rouge, the rising and falling, the scenery where the course is located – just beautiful. I expect just about every racing driver enjoys it. It was my favorite track from the beginning.

So it was very fitting that there, on August 30, 1992, he took his maiden victory.

The Class of 1992

Let’s take a stroll through the grid at Spa and see who was on it, starting with the world champion, Nigel Mansell, who had clinched his one and only title in the previous race at Hungaroring. That year, the Brit set a record for the most wins (9) and pole positions (14) in a single season. No one could stop the combination of the owner of the most famous mustache in the history of the sport and the phenomenal Williams FW14B.

The only person who hypothetically had a chance was his teammate, Riccardo Patrese. The Italian veteran, a six-time race winner, held the record for the most race starts for over a decade after his retirement, yet he could not match his teammate. On the Beyond the Grid podcast he mentioned that actually preferred the previous car, the 1991 challenger, despite the car lacking active suspension and traction control. This preference likely stemmed from a fact that he had outqualified Mansell in 1991. The following year, the Italian managed to achieve this on only on two occasions: Canada and Hungary.

At McLaren, the illustrious years had come to an end, and Ayrton Senna, a three-time world champion and F1’s biggest star at the time, instead of competing for the drivers' crown as he had been doing in the previous four seasons, he could only hope for occasional victories. By that point, he had secured two wins, in Monaco and Hungary. The Brazilian also got one pole position, which is quite staggering given that, already at the time, he was the all-time pole leader. Such were the joys of competing against the FW14B. Speaking of which, Senna desperately wanted to join the Grove team for 1993, and even offered Frank Williams to drive for free. Frustratingly for him, it didn’t come to a fruition.

1992 was the last season for Gerhard Berger as Senna’s teammate, with whom he had a very good relationship. He never beat the Brazilian over a season. Instead he outpranked him by, among other things, filling his friend’s bed with frogs or replacing his passport photo with a dick pick. Berger won in Canada in 1992 and was generally closer to Senna than in their two previous seasons together at McLaren. However, this was largely due to the ambitious Brazilian overdriving and taking more risks than usual. At Spa, the jovial Austrian announced his return to Ferrari for the 1993 season.

The Benetton driver Michael Schumacher, or the German Wunderkind as sometimes Murray Walker used to call him at the time, was yet to complete a full F1 season. He famously made his debut at Spa a year earlier for Jordan, stepping in for Bertrand Gachot, who had been arrested for spraying a London taxi driver with CS gas. A year later he returned to the circuit in the Ardennes with four podiums on his resume. Up to that point, his highest finishing position was second, achieved in both Spain and Canada. The German displayed considerable talent but also made some rookie mistakes.

In 1992, Martin Brundle joined the Wunderkind at Benetton, replacing the retired Nelson Piquet. Nowadays he’s known for commentating Formula 1, a job he has held since 1997, but he was also a decent driver. Even though the Brit was vandoorne’d in qualifying by his teammate (a feat he repeated by Hakkinen two years later), he managed to keep Schumacher honest throughout the season. This was largely due to his experience as a solid veteran, while the German was often too ambitious and greedy for success. At that point of the year, Brundle had secured two podium finishes and could’ve even won in Canada, but a transmission failure ruined his chances for victory.

Jean Alesi, a one-time race winner. How it pains my fingers to write that. The French Sicilian could have sat behind the wheel of the FW14B, winning races and championships, had he not chosen Ferrari over Williams at the end of 1990. This decision stands as one of the biggest "what ifs” in the history of the sport. In 1992, he performed very good in a relatively uncompetitive car, which encapsulates the story of his career.

Lotus had a very interesting driver lineup: Mika Hakkinen and Johnny Herbert. The future double world champion plus the future three-time race winner and a failure of a media pundit. Credit to the Brit, he outqualified the Flying Finn in 1992; however, he had to acknowledge the superiority of his teammate in races.

One man who didn’t line up for the start of the 1992 Belgian Grand Prix, but was present at the venue, was Damon Hill. The future world champion drove for Brabham, replacing the last female driver in F1, Giovanna Amati. He didn’t participate in the Belgian Grand Prix because the team had ran into financial difficulties and did not complete the season. During the weekend, Hill was busy knocking on doors and searching for a seat. Finally, at the end of the season, he secured it at Williams, where he had been working as a test driver since 1991.

Among the names that filled the headlines in 1992 and in the future, there were also other drivers, who had their glory years behind them. Like a three-time race winner Thierry Boutsen, or the 1985 championship runner up Michele Alboreto, or Aguri Suzuki, the first Japanese to stand on a podium and, to make it even better in his home race at Suzuka in 1990. There were also drivers who had a much more interesting story to tell than their stat lines, like Roberto Moreno and Karl Wendlinger. And who could forget James Hunt’s favorite, the one and only, Andrea de Cesaris?

The grid had a lot of color, character and personality.

The Absent One

Certainly, from the perspective of the driver market, the most important person did not compete in a single race in 1992. Alain Prost, after being released from Ferrari at the end of 1991, tested for Ligier but ultimately chose to take a one-year sabbatical.

Before the Spa race, rumors circulated about him signing a contract with Williams for 1993. The Frenchman in a team supplied by the French engine manufacturer Renault. Great marketing, but it was bad news for Mansell, who hadn’t gotten along with the Frenchmen when they both had driven for Ferrari, and who had no contract for 1992. Even worse news awaited Senna. According to the Brazilian, Prost had a clause in his contract that allowed him to veto the addition of his former teammate to Williams.

Obviously, the Brazilian was not pleased. He did not want to drive a car that had no chance of winning the championship, and to make matters worse, it also lost the Honda engine. (The Japanese manufacturer exited the sport at the end of 1992.) Senna considered a sabbatical and even tested for an IndyCar team Penske. In the end, he stayed in F1. The Brazilian signed a five-race contract with McLaren and later continued to re-sign on a race-by-race basis.

It was Mansell who left for America. After lengthy and turbulent negotiations, he and the Williams team failed to reach an agreement. The entire process had a soap opera vibe that irked Hunt. The former world champion turned commentator, known for never shying away from expressing his opinion, at one point said Mansell should shut up and face Prost.

However, all of that happened later. At Spa, the entire saga of who will drive for Williams in 1993? was just beginning to unfold.

Cutting Edge

It would’ve been a challenge to find a pilot who didn’t want to drive for the Grove team. No surprise. Their car had no equals. The FW14B was, without a shadow of a doubt, a masterpiece. First and foremost, it featured active suspension, which Frank Dernie had designed in the late 1980s. Dernie had left the team in 1989, so the task of implementing his engineering marvel on the 1992 challenger was entrusted to Paddy Lowe and Williams test driver Damon Hill. It’s safe to say they did a fairly decent job.

The car was powered by the Renault V10, the engine of the 1990s. Coupled with Newey’s aerodynamics, a semi-automatic gearbox, and traction control, the result was a robust overkill. Williams were undoubtedly the best by a very wide margin. However they were not the pioneers in this field.

Ferrari were the first to introduce a semi-automatic transmission and traction control. The former, conceived by John Barnard, was a feature of the 1989 challenger, the 640. The latter was used first time at Estoril in 1990.

Ferrari introduced. Williams followed suit. McLaren lagged behind for a time. The team led by Ron Dennis, began the season with last year's car, the MP4/6B, which featured a manual gearbox. In Brazil, its successor, the MP4/7A, made its debut. This new car was finally equipped with a semi-automatic transmission, but it had to wait for traction control to the Hungarian Grand Prix.

The only top team without the fancy tech in 1992 were Benetton. Nevertheless, they also introduced something new to the sport. The characteristic, lifted nose, sometimes referred to as a “shark nose,” which Rory Byrne and the others had introduced in 1991, in the middle of the decade was copied by Adrian Newey himself.

The Competitive Hierarchy

At the top of the grid in 1992, there was an aristocracy and a peasant rest. The latter, meaning: McLaren, Benetton, and Ferrari, lagged significantly behind the former in qualifying.

How does this compare to other cars from the 1990s? According to the method illustrated in the graph, the fastest qualifying car of the decade is not the FW14B, but its successor, the 1993 challenger, which is 1.780% faster than its closest competitor, the McLaren MP4/8. Following them is the 1990 McLaren, which holds a 0.677% advantage over its Ferrari counterpart.

Even though qualifying is one thing, but the race is another, on Sundays, the outlook for McLaren, Benetton, and Ferrari was generally bleak. Instead of relying on their own pace, they often depended on the misfortunes of the formidable Williams team, as seen in Monaco, where a prolonged, unscheduled pit stop cost Mansell a victory. Typically, the top two spots on the podium were reserved for the cars numbered 5 and 6. Such was their dominance. Most of the time, the remaining teams were left to compete among themselves for the last step.

Before the Belgian Grand Prix, Williams took 8 victories out of 11 races, all scored by Mansell, who equaled the record for the most wins in a season, previously set by Senna in 1988. The team also finished 1-2 on 6 occasions.

Sun and Rain

The magnificent Spa circuit, which was still part of public roads at the time, welcomed the teams with sunny weather. Friday was warm and dry, with no clouds to disturb the clear blue sky. However, the day had a terrible start.

During the morning practice session, Ligier driver Erik Comas crashed at Blanchimont. The Frenchman hit the barriers at high speed, spun around, and stopped sideways in the middle of the track. The impact knocked him unconscious.

Senna was the first to arrive at the scene. The Brazilian immediately stopped, jumped out of his car and run to help the fellow driver. He turned off Comas' engine, which had been revving due to the floored throttle pedal pressed by the unconscious Frenchman, and held his head until help arrived. Later, in multiple interviews, Comas stated that Senna saved his life.

The newly crowned champion, Mansell, traditionally took P1 in qualifying, finishing 2.198 seconds ahead of Senna, 2.676 seconds ahead of Schumacher, and 3.012 seconds ahead of Patrese. The trio behind the pole sitter all spun during the session: the Brazilian at the entry of Bus Stop, the German in the braking zone before La Source, and the Italian in the chicane leading to the short main straight. Patrese stalled his engine after the pirouette, ending his session prematurely.

Alesi set the 5th fastest time. Following him were Berger, Comas' teammate Boutsen, Hakkinen, and Brundle.

In 1992, we still had two qualifying sessions held on Friday and Saturday, each lasting one hour. During each session, a driver had 12 laps at their disposal, and only the best times from both days counted.

Nobody improved on Saturday because the heavens opened and bombarded the circuit with a heavy downpour. The session served as practice for wet running.

Berger fell a victim to the slippery tarmac. The Austrian aquaplaned on the rundown to Eau Rouge, lost control, spun, and bounced off the barriers like a snooker ball before stopping in the middle of the famous corner. He exited the car unscathed.

The Ardennes Roulette

Even though Sunday began sunny, spots of rain were already visible during the formation lap for the 1992 Belgian Grand Prix.

The red light went off, the green came on and the cars took off. Well, almost all of them.

Berger didn’t move an inch. The transmission of his McLaren failed. The Austrian, disgusted, exited the car and removed the steering wheel, complicating the marshals' work more than usual. By the time the pack completed the first lap, Berger's McLaren was still partially on the grid. Safety? Nah, it’s 1992! Who gives a shit?!

At the start, Senna passed Mansell before reaching La Source. Schumacher fell behind Patrese and Alesi. Behind them, Hakkinen and Brundle overtook Boutsen. The Finn before the first corner and the Brit around the outside of it.

Schumacher made a quick work of Alesi on the Kemmel straight. In the process, the Benetton’s floor touched the tarmac. The friction shot bright sparks high above the car. The German was in fourth place as he approached Les Combes.

At the end of the first lap, 5 seconds separated the top 7 of Senna, Mansell, Patrese, Schumacher, Alesi, Hakkinen, and Brundle.

The order changed when the rain intensified during the next lap. The leading McLaren lost two positions to the superior Williams in the third sector. Mansell overtook Senna at Blanchimont and Patrese at Bus Stop. The new leader set the time of 2:18.821, which was 5 seconds slower than the opening lap due to the rain's impact. Unfortunately, conditions were only getting worse.

Place Your Bets

On lap 3, Mansell and Alesi pitted for wet tires. The Ferrari driver completed the next round ahead of the Brit. Mansell had a disastrous out lap – almost full 9 seconds slower than the Frenchman. Was it due to a lengthy tire change? Did he have an off track adventure? No idea. All I know is the outcome. The TV direction back then severely lacked compared to modern standards. However, for those who grew up watching the sport in the 1990s, everything was beautiful, awesome, the best ever, and better watch your mouth in their presence!

Alesi and Mansell crossed the finish line 13th and 14th on lap 4. During the same round, Schumacher boxed and, after exiting the pits, briefly separated the two, before losing a position to the Williams driver on lap 6.

Lap 5, Brundle and Hakkinen pitted, followed by Patrese in the next round. The Italian exited the pits ahead of Mansell, tiptoeing on cold tires. The ones on his teammate’s car were much warmer. The Brit took advantage and passed Patrese on the rundown to Eau Rouge.

At the end of lap 7, Senna, who stayed out, led the field 11 seconds ahead of Alesi. The Frenchman was holding up Mansell, while Patrese was delaying Schumacher. Brundle enjoyed some clear air in front of him and set 2:17.754, which was exactly 2.3 seconds faster than Senna.

The conditions continued to deteriorate. Wet tires were the safer option, but the leader was not interested in playing it safe. Senna wanted only one thing: victory. The Brazilian gambled on the weather and stayed on slicks. He went all-in, hoping for the rain to subside and for a pit stop advantage once the track dried out.

The Hounds and the Hare

At the beginning of lap 8, the battle for second place ended in misery for Alesi. Mansell got right on his gearbox on the main straight, threatening an attack on the inside. The Frenchman covered that option and returned to the racing line before La Source. All fine, except Mansell was already there, with his front tires alongside Alesi's rear tires after switching to the outside. They banged wheels. The Ferrari got a puncture. The Frenchman spun out and stalled the engine. Game over for him. The Williams emerged unscathed, however Mansell was subsequently overtaken by his teammate.

A modern eye could see in Alesi’s defensive maneuvers swerving in the braking zone and crowding… So just racing in 1992.

The collision ultimately benefited Senna, who improved his time and went below 2:20, a time he had been setting in the 5 previous laps. Meanwhile, Patrese, now in P2, was 3.22 seconds faster.

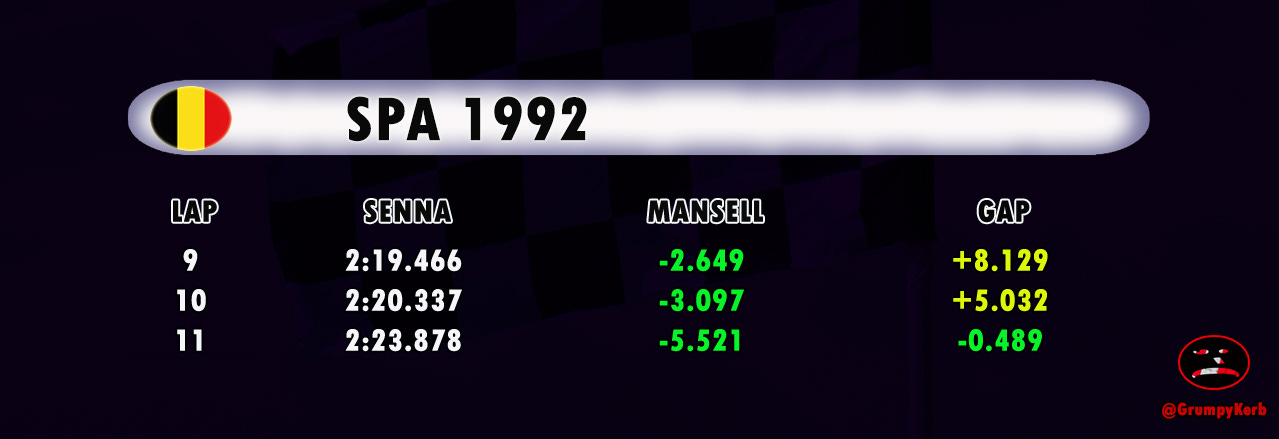

On lap 9, the front of the field shuffled once more. Mansell overtook his teammate in Bus Stop. That of course, played into Senna’s hands by slightly slowing down his pursuers: the two Williams and the two Benettons. The problem was, Mansell, even though he had to battle his teammate, still managed to go 2.649 seconds faster than the leader.

To make matters worse for Senna, the rain did not let up; in fact, it intensified. The Brazilian’s lead quickly dwindled.

It took Mansell 3 laps to catch and overtake the leader, thanks to the grip advantage of wet tires. The Williams had a superior exit from the second Stavelot, positioned itself alongside after Blanchimont, and outbraked the McLaren in Bus Stop.

Still, it wasn’t the end of Senna’s heroics. He kept Patrese behind for the majority of the next lap. Even though the Italian had a much better run out of Eau Rouge, he couldn’t get past at the Kemmel straight. Senna wisely stayed on the drier racing line, forcing the Williams driver to brake on the inside, where there was more water. Additionally, the Honda V12 engine proved resilient against the challenge from the mighty Renault.

Senna defended his position by cutting across in front of Patrese at Rivage and in the no name corner, but at the end of the second sector, he ultimately had to capitulate. The Italian overtook him around the outside of the first Stavelot.

On lap 13, the Ford V8 engine powering the Benetton tried his chances at the Kemmel straight against the Honda. To no avail. Senna used the tactics of cutting across against Schumacher at Malmedy. Successfuly. The German was closely followed by Brundle and Hakkinen, who had benefited from the McLaren driver holding up the faster cars and caught up to the Benettons.

Schumacher got alongside Senna on the short straight leading to Fagnes and outbraked him on the outside just before the corner. At the same time, Brundle threatened to attack the McLaren on the inside. What the Brit couldn’t achieve going into Fagnes, he did at the exit of the fast chicane. Hakkinen also found a way to overtake the Brazilian, executing the maneuver on the inside of the first Stavelot.

Senna lost three positions in two corners and nearly 15 seconds to Mansell while defending against Patrese and others. The gamble didn’t pay off. The Brazilian finally pitted for wets from P6 on lap 14, emerging in 13th place, 50 seconds behind the leader.

The Patrese Train

The race settled down. Mansell, in complete control, was steadily building an advantage over his teammate, who, rather than chasing the leader, had to concentrate on what was happening behind him.

The Benettons were handling pretty well the treacherous conditions. Hakkinen couldn’t keep up with them and fell behind.

Schumacher quickly erased the gap to Patrese. Brundle followed suit. However the pursuit stalled when less than 1 second separated the German driver from the Williams. He couldn’t get close enough to make a move. Schumacher got stuck behind Patrese. Brundle got stuck behind his teammate.

The Italian locomotive was pulling the two cars along the picturesque track for several laps.

Time to Change

On lap 27, the leader finally broke the lap record that Senna had set on the opening round. Mansell went around Spa in 2:11.729. The conditions, and consequently the lap times, were consistently improving.

In the middle of the pack, Senna was busy saving his race. He overtook de Cesaris on lap 16 for P12. Then he used the clean air to climb up to 7th place, as four drivers ahead of him had pitted for slicks. The Brazilian followed their lead.

It was the right idea. On lap 29, Senna set 2:05.960 and beat the previous fastest lap, briefly held by Patrese, by 3.175 seconds.

The weather switched allegiance. Slicks were the way to go.

Blisters and Blistering Pace

A minute before Senna recorded the fastest time, Schumacher went off track at the first Stavelot. The German glanced at Brundle’s rear tires as his teammate passed him. He saw blisters and instantly made the decision to box for slicks. This must have been an eureka moment, as on his second lap out of the pits, Schumacher clocked 1:59.824, surpassing Senna’s time by 6.175 seconds. No one else managed to complete a lap around Spa in under 2 minutes, except for the German.

On the same 32nd round leading Mansell, still on wets, had set 2:07.198 and Senna improved to 2:03.141.

Brundle changed tires one lap after his teammate. 2:04.129 was his first flying lap on slicks. Patrese, in turn, pitted a lap after the Brit and only narrowly avoided the undercut. Brundle got stuck behind the Williams driver for the remainder of the race.

Schumacher made use of clean air and went even faster: 1:58.416. Still the only driver under 2 minutes. The closest one to him again was Senna with 2:01.172.

On the very same lap, number 33, Mansell finally pitted for slicks. Too late. The Williams driver had enjoyed 11.968 second lead over Schumacher before the German dove into the pits. 5 rounds later he found himself 5.713 seconds behind the new leader.

Luck Favors the Underdog

However, the race was far from over. Mansell still had the FW14B underneath him and 10 laps to catch Schumacher. Backmarkers helped him in this endeavor. The German was first impeded by a Larrousse driven, ironically, by Gachot (lap 35) and later by Stefano Modena in a Jordan (lap 38).

Schumacher and Mansell were improving their lap times while skillfully navigating through the traffic. The Williams was closing in on the Benetton. By the end of the 38th round, only 3.002 seconds separated the two drivers. It seemed to be only a matter of not “if”, but “when” Mansell would catch up to Schumacher, utilizing his superior straight-line speed to overtake the German and take his record-breaking 9th win of the season.

None of that happened. The nail-biter was abruptly halted just before the final duel. Lady Luck pulled the plug on the excitement. Mansell had to wait longer for his 9th win. His engine began to misfire on the 39th round. He lost 12 seconds to Schumacher, who, to add insult to injury, set the fastest lap of the race - the first in his career.

The leader, unencumbered by any threats, controlled the race and finished well ahead of the wounded Williams. Patrese and Brundle crossed the line 3rd and 4th.

Senna, who experienced numerous adventures that day and even spun on lap 31 at the exit of La Source while overtaking JJ Lehto, meticulously worked his way back into the points. On the penultimate lap, the Brazilian passed Hakkinen for P5 at Les Combes.

The Finn took the final point, a modest reward for executing an excellent race and finishing as the best of the rest. The retirements of Berger and Alesi certainly helped him, but that’s what smaller teams, Lotus being one of them in 1992, needed to score. On pure pace they stood little chance.

The 79th Formula 1 Race Winner

Schumacher likely would not have won without Mansell's misfortune and his decision to stay out on wet tires for too long. Without a stroke of luck and the mistakes made by the drivers, there would have been little that could be done against the mighty FW14B.

However, the aforementioned two factors were only parts of the German's success - more precisely, two quarters. The other components were Schumacher's ability to think on his feet and his blistering pace out of the pits. He microwaved the slicks on the out lap, and the tires rewarded him with ample grip on the semi-wet circuit.

Schumacher’s victory heralded the dawn of a new era while simultaneously marking the twilight of the old one. The Benetton B192 was the last car equipped with a manual gearbox to win a race in Formula 1.