The Passage of Time Redefines the Role of Formula 1 Drivers

A few reflections on how the evolution of the sport has changed the challenges faced by pilots.

Time flies, as the old saying goes. Taken literally, this adage holds particularly true in the world of Formula 1, where a stopwatch determines the hierarchy of teams and drivers during a qualifying session, grand prix, or an entire season. However, this is not the intended use of the idiom, of course.

It primarily reflects the human perspective on the rapid passage of time, both in the short and long term. Eras begin and conclude, champions rise and fall, teams fluctuate within the competitive order, regulations change, technology advances, and the sport becomes increasingly complex. These changes and improvements can also be quantified with a stopwatch.

Michael Schumacher took the pole position for the 1995 Japanese Grand Prix with a time of 1:38.023. Three decades later, at the same venue, Max Verstappen accomplished the same feat, setting a new lap record at Suzuka with 1:26.983. Thirty years of changes, advancements, and the overall evolution of the sport account for the 11.040 seconds that separate the pole positions of these two all-time greats.

Today’s Ceiling Is Tomorrow’s Floor

Time flies; the sport evolves, transforming what once seemed like an impossible challenge into a mere formality.

In 1999, during qualifying at Spa, Jacques Villeneuve and Ricardo Zonta made a bet that they would take Eau Rouge and Raidillon flat out, which was quite a challenge, to say the least. The bet ended in a draw, as neither of the BAR teammates lifted off the throttle, and neither made the corner. However, in my book, they undoubtedly secured a spot in the top 5 most spectacular crashes of the season.

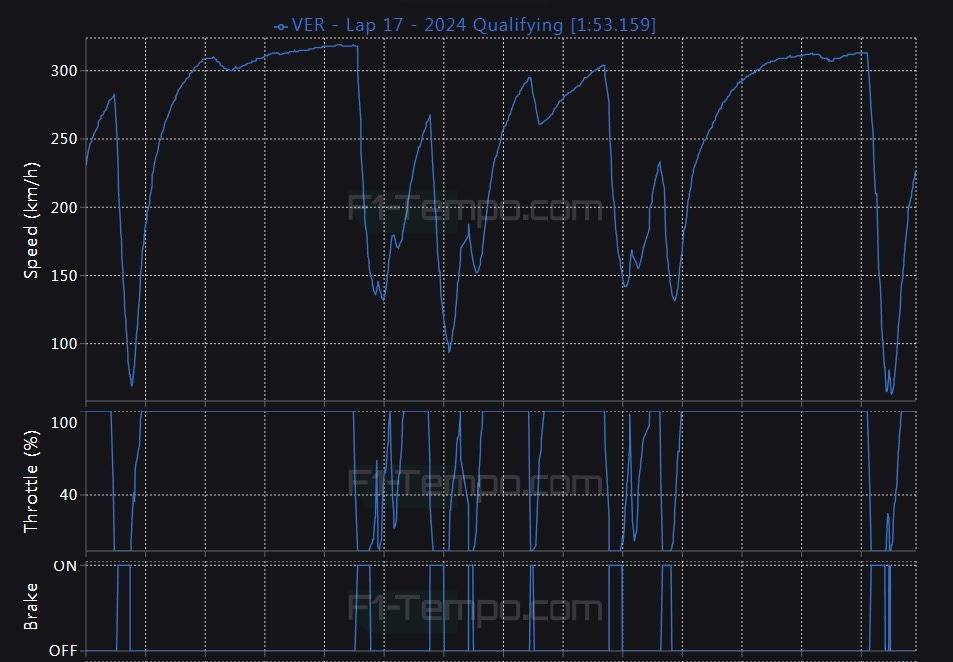

Nowadays, taking Eau Rouge and Raidillon flat out is something drivers do on a regular basis, simply because they can. Although this complex of corners remains dangerous, it is significantly easier than it was two or three decades ago. Last year, during qualifying, Verstappen even took it flat out in the wet. The Dutchman's throttle pedal remained floored from the exit of La Source to the braking zone before Les Combes.

Verstappen's teammate, Sergio Perez, along with the Mercedes duo of Lewis Hamilton and George Russell, also went pedal to the metal, while Charles Leclerc and Oscar Piastri only eased off by 1% in certain sections of the two famous corners.

This shouldn't come as a surprise. Modern cars, while more physically demanding due to higher speeds and the stronger g-forces that drivers' bodies must endure, are easier to handle than those from the 1990s. This is primarily because they have more downforce and grip.

Optimized by Technological Progress

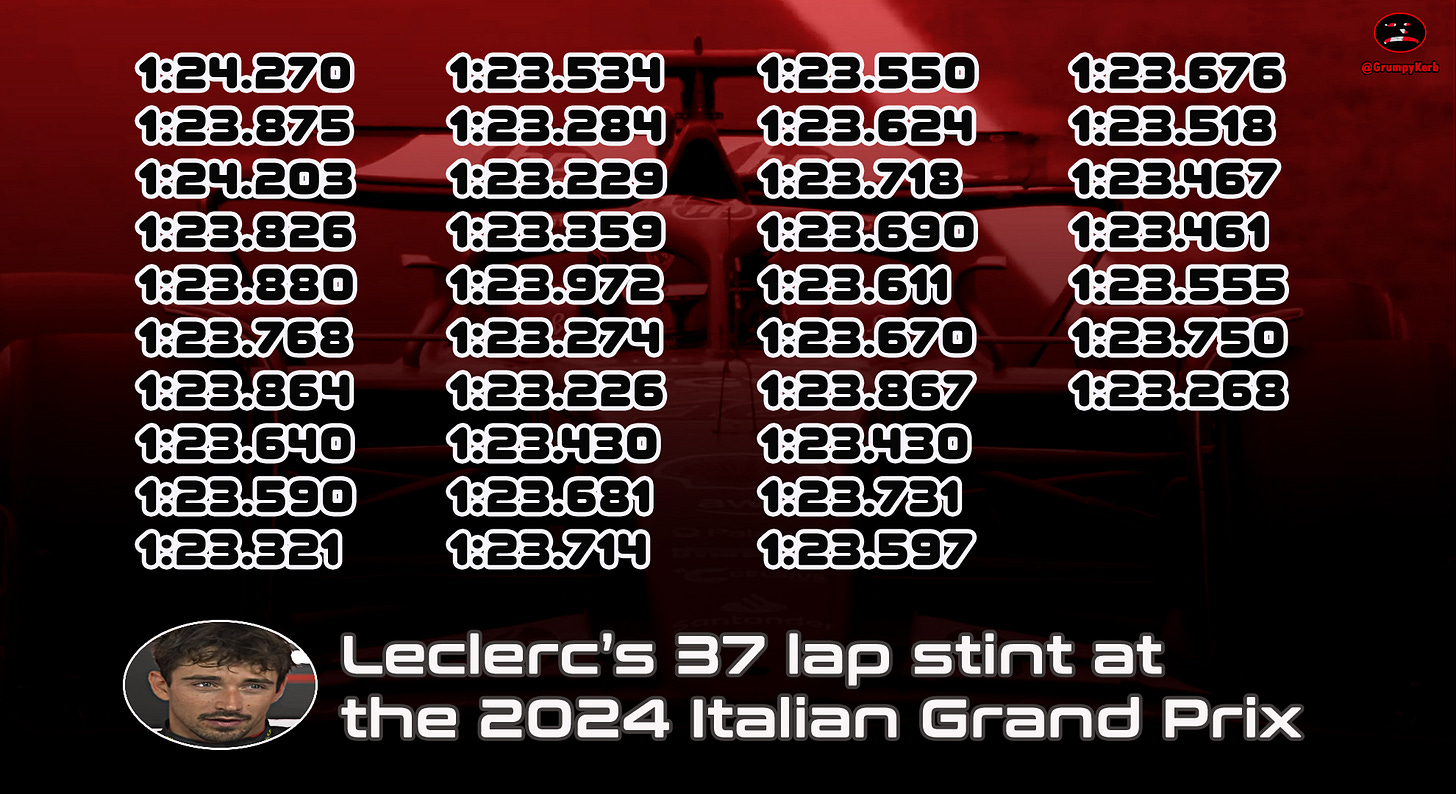

Last year, we marveled at Leclerc’s magnificent and victorious 37-lap stint on hard tires (excluding the out lap) during the Italian Grand Prix. The Ferrari driver, with the precision of a Swiss watchmaker, circled around the Monza circuit in the 1:23 range on all but two tours, to beat the superior McLarens and win in front of the tifosi.

A splendid performance and marvelous consistency, without a shadow of a doubt. Leclerc has rightly been lauded for this stint.

Maybe I’m foolish, but I don’t think you’ll find an equivalent from the 1990s, or at least not one as consistent. Specifically, before 1994, the refueling era shifted its focus from managing tires and other things to pushing hard to create a gap before a pit stop. Naturally, when you’re “pushing like a hell,” as a famous Italian train driver once said, you’re less likely to set as consistent lap times compared to when you’re driving to a delta.

Speaking of which, I don’t believe there was such a concept in the early 1990s. While this is an educated guess, target lap times emerged with advancements in computer simulations, which have increasingly optimized race strategies. Nowadays, the entire "game plan" revolves around real-time updated simulations.

So, Alain Prost, Ayrton Senna, Nigel Mansell, and other prominent drivers of the time, hadn't been setting as consisted times like Leclerc did last year at Monza, simply because they had never intended to do so. Furthermore, their pit walls were not supported by complex simulations that recommended target lap times, which could be communicated via radio. They also lacked advanced dashboards that provided real-time information about their pace. Instead, they had only basic steering wheels with speed and RPM displays.

Their machines did not generate as much downforce and grip as modern cars; therefore, their lap times were less consistent. Additionally, reliability concerns often weighed heavily on them, much like the proverbial monkey on one's back. Consequently, unlike modern drivers, they frequently had to manage not only tire performance but also various mechanical issues, both minor and major.

More Than Meets the Eye

The quality and reliability of cars, which have undoubtedly improved over the decades, are not the only changes that have benefited modern drivers compared to their predecessors. Some of these changes are less obvious than those already mentioned, such as the decrease in the number of teams, for example.

There were 16 of them in 1992, which translates to 32 cars. However, only 26 qualified for a race, resulting in 6 more than today. A greater number of cars leads to increased traffic, which serves as a perfect segue to discuss backmarkers. Back then, they were quite different; some were even up to 4 seconds per lap slower than the leaders, necessitating that the front runners lap them twice or more during a single race.

The backmarkers did not always adhere to proper racing etiquette, as James Hunt often remarked. This was partly because there was no rule requiring backmarkers to allow faster cars to pass after three blue flags had been displayed; otherwise, they would face penalties. This rule was introduced three years later.

The absence of incentives to make it easy for the leading drivers resulted in some individuals being quite uncooperative. In 1992, there was a particular Finnish backmarker who would hold up the front runners for several laps and even collided with them on occasion when they attempted to pass, as he did with Jean Alesi during the Spanish Grand Prix. Interestingly, this obstinate Finnish backmarker went on to become a double world champion in the late 1990s.

So, imagine Mika Hakkinen at the peak of his stubborn phase, roaming on the track without any blue flags, while Leclerc attempts to lap the delinquent. Now, ask yourself: With such an obstacle in his way, would the Ferrari driver be able to maintain consistent lap times?

The Blessings of Reliability

Coming back to reliability, which is currently at its best, it used to present challenges both directly and indirectly. When an engine failed, it would leave oil on the track, creating a mini skating rink. For instance, I recall the first race I watched: the 1994 Monaco Grand Prix.

Schumacher led the race from pole position and was approaching a Tyrrell, driven by Mark Blundell, to lap him. On the main straight, Blundell's car began to emit smoke like a steam locomotive. He retired in the small runoff area near Saint Devote. In that corner, Schumacher slid on oil that had leaked from the Tyrrell but managed to catch the car and avoid crashing into a barrier.

The German had witnessed Blundell's engine giving up the ghost, so he was likely extra cautious when approaching Saint Devote. Gerhard Berger, who at the time was approximately 25 seconds behind Schumacher, didn’t have this luxury.

The jovial Austrian lost control of his Ferrari and ended up in the same area where Blundell had retired. Fortunately for Berger, he didn’t damaged the car or stall the engine, allowing him to return to the track. At first glance, it seemed he had dodged a bullet—or rather, a mortar shell. However, the problem was that his tires were still coated in oil.

Berger experienced a considerable grip deficit compared to McLaren's Martin Brundle, who arrived at the scene just as the Austrian returned to the track. The Brit relentlessly pressured the struggling Ferrari through several corners, and at the first opportunity, he overtook it on the outside of Mirabeau. This is how Berger lost P2.

This type of wild card has been almost completely eliminated from Formula 1, if not entirely. To some extent, it has been replaced by neutralization; safety cars are now more frequent due to stricter safety standards. The same is true, to an even greater extent, for red flags.

Grass and Gravel vs. Tarmac

The other well-known example of oil-induced slipperiness involves the leading Ferraris of Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello, who lost control on the fluid left on the track by Olivier Panis's blown engine during the 2001 Sepang circuit race. In the blink of an eye, their 1-2 position turned into a 3-7.

It likely would have cost them only a few tenths, if back then, there had been as many runoff areas as there are today. Although the old good gravel has made a comeback in recent years as a mean of enforcing track limits, modern drivers still have more comfort zones beyond the white lines that were unavailable to their predecessors from two or three decades ago.

Psychologically, it is clearly easier to push the limits, especially considering that crossing a white line with your wheels or overshooting a corner does not result in disastrous consequences. Tarmac doesn’t cost time nor potential damage, and it completely eliminates the risk of being beached, like Felipe Massa at Sepang, back in 2008.

Grass and gravel have also hindered many discussions about racing standards that have been dominating social media lately. Drivers who attempted to pass on the outside often backed off upon realizing that their rivals would force them off the track. Hardly anyone took the risk of staying on the outside, only to complain vehemently on the radio after being pushed off the circuit, simply because bailing out was the best available option.

Then and Now

You may conclude that this post seeks to devalue modern drivers, but that is not the case. I do not believe they have it easier in every respect. I have previously mentioned that today’s cars are much more physically demanding, which means that in this regard, Verstappen, Leclerc, and others have it harder than the stars of the 1990s. A similar argument can be made about the Monaco Grand Prix.

Although modern cars on average are generally less snappy and more cooperative, they are also larger and wider. This, combined with the fact that the circuit hasn’t significantly changed over the years and that the streets of the Principality remain as narrow as they were in the past, makes Monaco more challenging, in my opinion. After all, it is easier to maneuver nimble, lighter vehicles through the claustrophobic spaces than the heavy, cumbersome speedboats that have been used since 2017.

Furthermore, today’s drivers have much more to focus on than simply driving a Formula 1 car, which, needless to say, is quite demanding. Just watch Senna’s pole position lap at Monaco from 1990. Ignore everything else and concentrate on his steering wheel. Yes, it has only three buttons.

A lot less than a modern steering wheel, which also includes numerous knobs and a dashboard filled with a gazillion information drivers have to process, while traveling at 200 km/h. Consequently, I would argue that contemporary Formula 1 racing is more mentally demanding.

Apples and Oranges

“A decade is a long time. In motor sport it's forever. It's centuries,” said Pat Symonds on the Beyond the Grid podcast. And that’s basically the essence of this post. Earlier this year, I discussed mathematical models and expressed my view that evaluating drivers within the context of their respective eras is more appropriate than creating an all-time hierarchy.

I hope that in all the previous paragraphs, I have presented compelling arguments for my case, which Symonds summarized in the following sentence: “When you're trying to compare the drivers [across decades], you're really looking at a very different sort of sport almost.”