The Mighty Mercedes Engine

A look at the circumstances surrounding the impressive reign of the best power unit of the 2010s.

When the 2014 season began, it became painfully obvious to top teams like Red Bull and Ferrari that they were nothing more than mere side characters in the Mercedes show. The Brackley team was far ahead of the competition, as if their challengers were the only Formula 1 cars on the grid, while others fielded machinery from feeder series. From the first race in Australia, it was clear to everyone that winning both titles would be as hard for Mercedes as lifting a single finger.

Although Mercedes' dominance is primarily attributed to their engine, it wasn’t the power unit alone. The chassis also had to be good and some really exceptional people worked on it, like Aldo Costa, one of the most underrated designers. As Rory Byrne's right-hand man, he played a crucial role in the development of the Ferraris in the early 2000s and later put his brilliant mind to work at Mercedes.

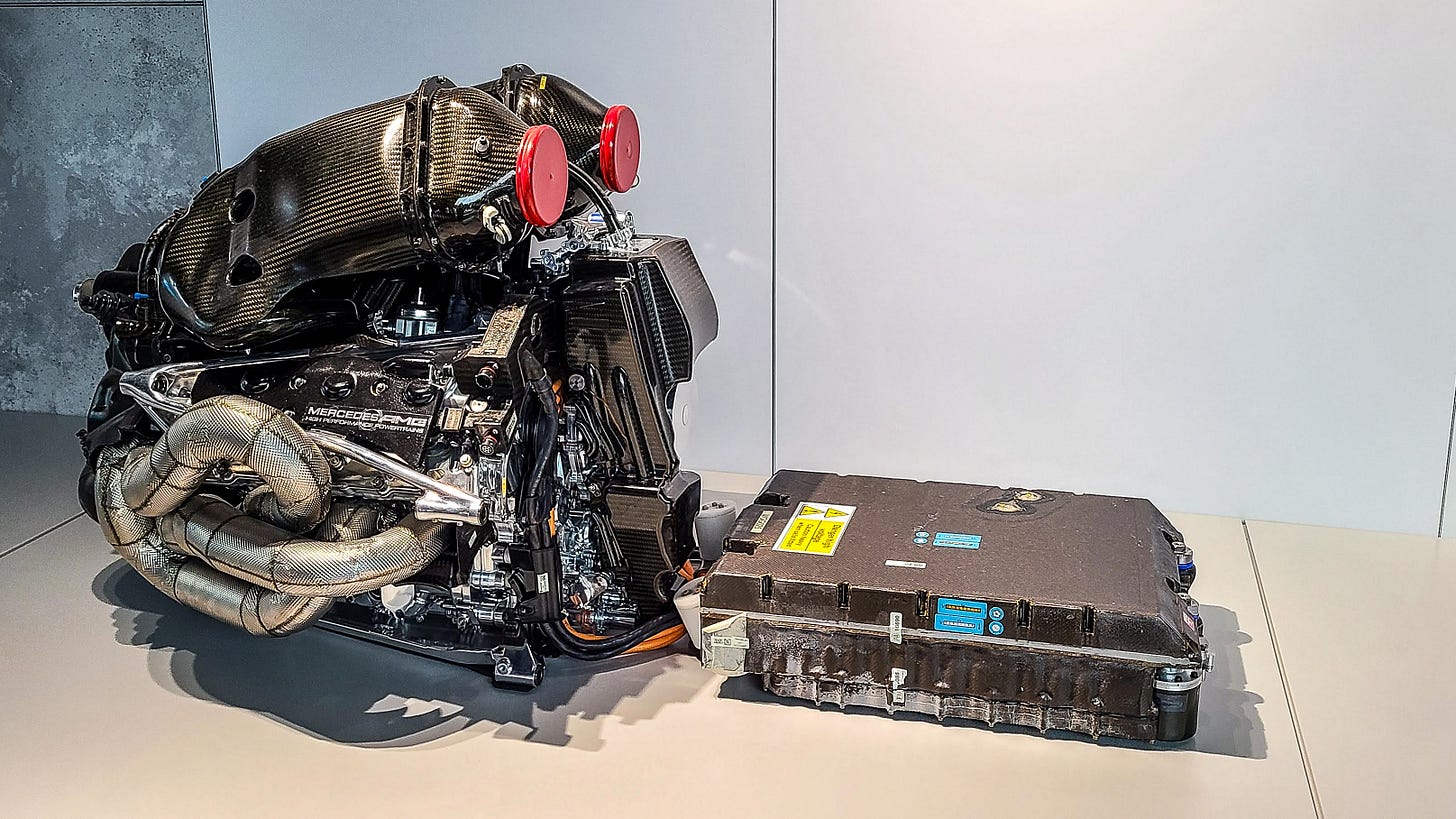

Yet, the primary source of their competitive advantage was, of course, the power unit. A true masterpiece of engineering, it was designed by a team led by Andy Cowell and Ben Hodgkinson, and it was undoubtedly the best engine of the 2010s. Its excellence was such that its reign continued until 2021.

The engine may have been even more powerful than Mercedes showed. The team kept it concealed due to concerns about potential intervention from the FIA. They were actually deliberating on how much to increase its power during Q3, as Paddy Lowe disclosed a few years ago. “Through most of 2014, that engine was never on full power for qualifying,” admitted the former Technical Director at Mercedes.

Customer Service

Of course, Mercedes were not only manufacturing power units for themselves, but also supplying them to their customers. Technically, the engines were identical; however, they did not always operate in the same manner.

In 2015, Lotus was one of three teams supplied by Mercedes. During the race in Belgium, their driver, Romain Grosjean, was closing in on third-place Sebastian Vettel. According to Matthew Carter, a former CEO of Lotus, Mercedes boosted the Frenchman’s charge by providing him with an additional engine mode, which made him, on average, 0.8 seconds faster.

After the race, Grosjean told the team that the car had never performed like that before. “It makes sense,” said Carter. “The minute your car is going faster your aero is working better, your tyres are better, you don’t have to brake as late. Every part of the car works better because he was in this mode.”

If you are wondering whether situations like the one described above are still permitted in Formula 1, the answer is no. In 2018, the rules were clarified, and since then, the engines must not only be of the same specification, but there must also be no restrictions on engine modes for customer teams.

Ahead of the Curve

Mercedes enjoyed a huge competitive edge partially because they had been ahead of schedule compared to other engine projects, as revealed by Ross Brawn, the Team Principal from 2010 to 2013, in his book Total Competition:

One of the things that became apparent to us at Mercedes during that period building up to when the new engines first raced in 2014, was that every time we asked the FIA for an interpretation or clarification of the engine regulations, it became clear we were the first ones to ask. This told me that we were ahead of the game compared with the other engine manufacturers. We were putting the work in early on the engine project when everyone else seemed to think there was plenty of time. They thought there was ample opportunity to get this job done. But at Mercedes we knew that we were going to run out of time. So the early work was vital. People like Thomas Fuhr, who was the manager at Mercedes High Performance Engines at the time, he was good at getting the foundations of all that work done. Making sure all the budgets were in place, making sure everything was there and pushing hard early on.

Another key aspect that Brawn mentions in his book is the existence of a separate team working on the 2014 car, with Cowell leading the engine group and Geoff Willis overseeing the chassis design. This approach ensured that the power unit and aerodynamics were fully integrated from the outset. For instance, the layout of the cooling system enabled Mercedes to implement the unique split turbo design.

The “Started Early” Narrative

The fact that Mercedes began developing the new engines early, ahead of schedule compared to their competitors, and their overall dominance at the start of the hybrid era likely contributed to the "started early" narrative. According to it, the Brackley team started working on the V6 turbo power unit well before the new regulations were finalized, and during the negotiation phase, they lobbied for the rules to align with their design.

The narrative is very easy to debunk; all that is required is a good internet search engine.

Mercedes F1 engines are manufactured in a factory located in Brixworth. Officially, it is owned by Mercedes AMG High Performance Powertrains, previously named High Performance Engines, as referenced by Brawn. The company releases its financial statements annually, which are publicly available. In the statement dated December 31, 2011, in section Director’s report the following is written:

Overall turnover has increased to £122.1 million (2010 £81.7 million). This was primarily due to the re-introduction of KERS for the three Formula One teams and the development activities on the 2014 V6-Power unit following the publication of the FIA technical regulations in June 2011.

For the record the rules indeed were approved by the governing body’s World Motor Sport Council in June 2011.

Unsurprisingly, designing and developing a new engine incurs significant costs. If Mercedes had begun the process as early as the narrative suggests, their turnover should have increased prior to the finalization of the new regulations, rather than afterward.

Since 2007?

The “started early” narrative gained momentum in 2017, fueled by comments from a former Ferrari president. According to Luca di Montezemolo, Niki Lauda revealed to him that Mercedes had been developing their V6 turbo engine since 2007.

Let's examine the financial statements for 2007.

Overall turnover has decreased to £80.7 million from £86.8 million due primarily to the success of the ongoing “cost down programme.”

Cutting costs would be a rather counterproductive approach to initiating a new engine project, I must say.

To be honest, I don’t believe di Montezemolo lied; he simply misinterpreted the words. Here’s why: in 2008, turnover increased to £96.9 million due to the development of KERS, which was introduced in the following season.

KERS is synonymous with MGU-K, a term that has been used since 2014. It is one of the two energy recovery systems utilized in Formula 1's hybrid engines, the other being MGU-H. Both systems convert kinetic and thermal energy into electrical energy. Therefore, it is accurate to say that Mercedes began developing a crucial component of the future V6 turbo engine well before 2011. However, this also applies to Ferrari and Renault, as both teams implemented KERS in 2009.

I believe Lauda mixed up the years, and di Montezemolo misinterpreted his words.

The Favorable Circumstances

The Mercedes power unit was far ahead of the competition in 2014. To add insult to injury for Red Bull and Ferrari, the engine advantage was maintained through the token system.

The costs of powertrain development can spiral out of control. To mitigate this issue, the FIA introduced the aforementioned system as part of the 2014 regulations. Here is how it worked, as explained by Ian Parkes in 2016:

In short, the power unit is broken down into 42 parts, with each of those allocated a token 'weight' from one to three depending on importance, and with the entire system comprising 66 tokens.

For example, should a team choose to develop the oil pressure pumps it would have to use one of its available tokens, whereas to improve combustion - defined as ports, piston crown, combustion chamber, valves geometry, timing, lift, injector nozzle, coils and spark plugs – requires three.

Prior to 2015, certain parts that amounted to five tokens were 'frozen', allowing scope for development of all the remaining parts, totalling 61 tokens.

Again, to avoid unlimited improvements, for 2015 the teams were allowed to use a maximum of 32 tokens, equating to 48 per cent of the power unit.

Essentially, it resembled a semi-engine freeze.

Of course, when one power unit is significantly ahead while the others can only develop at a limited pace, it naturally benefits the leading engine.

The Politics

That’s why Bernie Ecclestone, the head of the commercial rights owner at the time, sought to ease the restrictions for 2015. He had the support of Red Bull, Ferrari, McLaren, and the FIA President, Jean Todt. However, for the “ease” to become part of the regulations, unanimous approval from the F1 Commission—which consists of the commercial rights owner, the governing body, and the teams—was required.

Toto Wolff, who succeeded Ross Brawn as the boss of the team, was unsurprisingly opposed to it. The Austrian justified his veto by citing rising costs, which would prevent Mercedes from supplying their customers with the same specification engine at the same price. Furthermore, he argued that the “un-freeze” wouldn’t necessarily ensure that other manufacturers would close the performance gap.

The attempt failed and the status quo continued to be a thorn in the side of the competition. In 2015, Christian Horner even urged Ecclestone and Todt to eliminate the requirement for a voting process to change the rules, as it was being held hostage by self-interest.

Ultimately, Wolff conceded, and in 2016, an agreement was reached to eliminate the token system for the following season. It took two years of complaints, declining TV ratings, and even Ecclestone's threat to introduce a cheap alternative engine.

No Longer the Class of the Field

The competition finally could catch up, but Mercedes still enjoyed the best power unit, which was only briefly surpassed by Ferrari in 2018-2019 due to some fuel filter sorcery and was challenged by Honda in 2021.

Things have changed in 2022. Since the reintroduction of ground effect, the power units produced in Brixworth are no longer considered the gold standard. The precise engine hierarchy remains uncertain; however, calculations conducted by Auto Motor und Sport at the beginning of 2022 indicated that, in terms of power, Ferrari was 5 hp ahead of Honda, while Mercedes lagged 10 hp behind the Italians.

The calculations indicate that we have achieved engine parity, as the margins between the top three power units are minimal. Furthermore, the current engines have been frozen since mid-2022, allowing manufacturers to concentrate entirely on the 2026 power units.

Why did Mercedes lose its competitive edge?

I don’t know for sure, but the most obvious reason is the brain drain: Cowell's retirement (he recently returned to the sport at Aston Martin), and Hodgkinson's departure to Red Bull.

The other reason, I think, is the small yet significant regulatory change—the transition from E5 to E10 fuel. To clarify, in 2022, the ethanol content in fuel was increased from 5% to 10%. Hywel Thomas, the head of Mercedes' factory in Brixworth, referred to this as “the biggest change in hybrid era.”

It appears that Ferrari and Honda have adapted better.