A Staunch Defense of Damon Hill's 1995 Season

Too much blame has been placed on the driver, while his team has strangely escaped criticism.

1995 was not a good year for Damon Hill. For the second time, he finished as the runner-up to Michael Schumacher. Losing is inherently frustrating in itself, but the manner in which he lost and his performance throughout the season attracted a torrent of criticism. This led to rumors that Williams might replace him with Heinz-Harald Frentzen for 1996.

On the surface, the criticism is well warranted. Williams provided him with the fastest car, which secured 12 pole positions out of 17 races. All he had to do was deliver. Well that part didn’t pan out very well. At times, Hill, when compared to Schumacher, resembled Lando Norris next to Max Verstappen, if you prefer a modern analogy.

Although largely true, I believe that this perspective is overly simplistic. The reality was far more complex. The avalanche of criticism should have also crushed the team. They had many issues to address, yet it seems that this crucial aspect has been overlooked, and all the blame for 1995 has fallen solely on the driver's shoulders.

Hill was very good in the first 7 grand prix. It was only after the ill-fated dive-bomb attempt on Schumacher at Silverstone, when his performance went south. Prior to that incident, it was primarily the team's shortcomings that prevented him from leading the standings for more than one race.

From the Rain to the Gutter

Let’s not sugarcoat it; Hill provided his critics with plenty of ammunition from the British Grand Prix onward. However, upon closer examination, at least a quarter of that ammunition turned out to be blanks.

In the next race in Germany, he spun out of the lead at the beginning of the 2nd lap. At first glance, it may appear to be a driver error; however, that is not necessarily the case. Williams later revealed that Hill's left-hand driveshaft exhibited unusual wear. This may explain why his rear tires locked, causing the car to catapult off the track and into the tire barrier.

Then there was the hectic and turbulent Belgian Grand Prix, where he finished 2nd, to his credit. Nevertheless, Hill certainly made his job more difficult by spinning out during Saturday's qualifying, speeding in the pit lane during the race, and performing a pirouette at La Source, after the Safety Car restart.

The Crash and the Collisions

Things didn’t get any better in the subsequent event at Monza. The Brit collided with Schumacher, resulting in both of them being taken out of the race. However, there is more to this incident than meets the eye. The Williams driver was unsighted by none other than the legend himself, Taki Inoue.

The German lapped the backmarker. Closely following him Hill, attempted to do the same while heading into Variante della Roggia. He moved to the inside, but a moment later, Inoue did the same, forcing the Williams driver to switch to the outside. Focused on the Japanese, Hill braked too late and boom. It was game over for both him and Schumacher.

It’s rather difficult to focus on your braking point and decelerate the car safely when a backmarker alters their line just before the braking zone.

At the Nurburgring, he had a chance to win, but an incident with Jean Alesi forced Hill into an unplanned pit stop for a new nose. The Brit dove to the inside at Sportwart, but the Frenchman did the Senna: he chopped across and took the racing line as if no one were there on the inside.

No action was taken against either driver. At that time, these types of collisions were regarded as racing incidents.

Hill's race was ruined, and he ultimately finished before reaching the chequered flag. Near the end, he crashed while in P4. He went too wide at the exit of the same corner where he had previously collided with Alesi. As Hill accelerated, the rear wheel spun on the damp kerb, causing the car to snap, spin, and cut across the track before going off and hitting the tire barriers.

Little in Japan

Schumacher clinched the championship by winning the Pacific Grand Prix in Aida. Hill started the race from P2, one position ahead of the German, and even gave him a taste of his own medicine by forcing him wide in the first corner. It seems Hill found satisfaction in this maneuver, but it ultimately backfired, as his defense against Schumacher left the door wide open for Alesi to pass.

That made Hill's race a bit more difficult, but not as much as the botched pit stop that dropped him from P3 to P9. Later, he was involved in an incident reminiscent of the one at Nurburgring. This time Eddie Irvine did the chopping. Fortunately, the Williams’ damaged front wing did not necessitate a change, nor did it significantly affect the car's pace.

Hill's final misery of 1995 occurred at Suzuka, where he first went off track at Spoon due to a light drizzle sprinkling that section of the legendary circuit. Later, he spun out and beached the car in the same corner.

To cut him some slack, he must have been quite jaded at that point in the season. Additionally, the car was far from competitive at Suzuka. Not only did Benetton have the upper hand, but so did Ferrari and McLaren.

These are all of Hill's major shortcomings following the British Grand Prix. Frankly, they are not as bad as I previously thought. Some of them are glaring, some of them are the so called 50-50s. The Williams team should also share some of the blame, though not as much as they did before Silverstone.

The Glitch

The opening race of the season marked the first frustration for the Williams driver. He led the race with 3 seconds cushion over Schumacher, whom he had leapfrogged in the pits. He was on a 2 stop strategy, while the German opted for 3. Although he enjoyed a comfortable position, it was just nice bad beginnings.

First, he lost the gear on lap 30, and then he spun off in Senna S due to a suspected gearbox failure. That’s what he stated after the race. I’m not sure whether the Williams team confirmed this. Perhaps I’m naïve, but I’m inclined to believe him.

The second part of Senna S, the right hander, or Turn 2 if you prefer it that way, is a relatively straightforward corner that seldom presents difficulties. However, Hill spun out violently, as if a section of the tarmac had suddenly transformed into a skating rink beneath his rear axle.

The Last Lap Gremlins and the Differential

Brazil was just one race. Hill bounced back and won in Argentina and San Marino. For the first time in his career, he led the championship, but it didn’t last long. Schumacher reclaimed the top spot in the standings in the very next race in Spain, partly due to his victory and partly due to Hill’s misfortune.

The Brit held P2 until the final lap, when he unexpectedly slowed down and fell behind Johnny Herbert and Gerhard Berger. Hydraulic problems were the cause.

Problems liked Hill so much that they accompanied him during the Monaco Grand Prix. The Williams driver started from pole position, he had secured by beating Schumacher by nearly 0.8 seconds. The Brit was on a 2 stopper, the German refueled only once.

Although Hill was driving a much lighter car, he was unable to pull away and establish the necessary gap. Schumacher effortlessly followed him for 23 laps, at times falling back by no more than 2 seconds. To add insult to injury, after Hill pitted, he encountered traffic and lost another position to Alesi. He would have finished 3rd if the Frenchman hadn’t been taken out by Martin Brundle.

Later, it was revealed that Hill had driven the entire race with a faulty differential, which must have significantly compromised his pace.

The Gearbox and the Backmarkers

The Canadian Grand Prix was not a redemption for Hill, as his car was less competitive than those of Benetton and Ferrari. However, he could have still managed to score points and even gained ground on his championship rival, as Schumacher faced an electrical problem. A pit stop lasting over a minute dropped the German from the lead to P7. The only problem was, that the Brit had retired a few laps earlier due to a gearbox failure.

So, the car failed on Hill one way or another in three consecutive races. Thankfully, in France, it didn’t present any unpleasant surprises for its driver. Now it was time for the strategists to screw up.

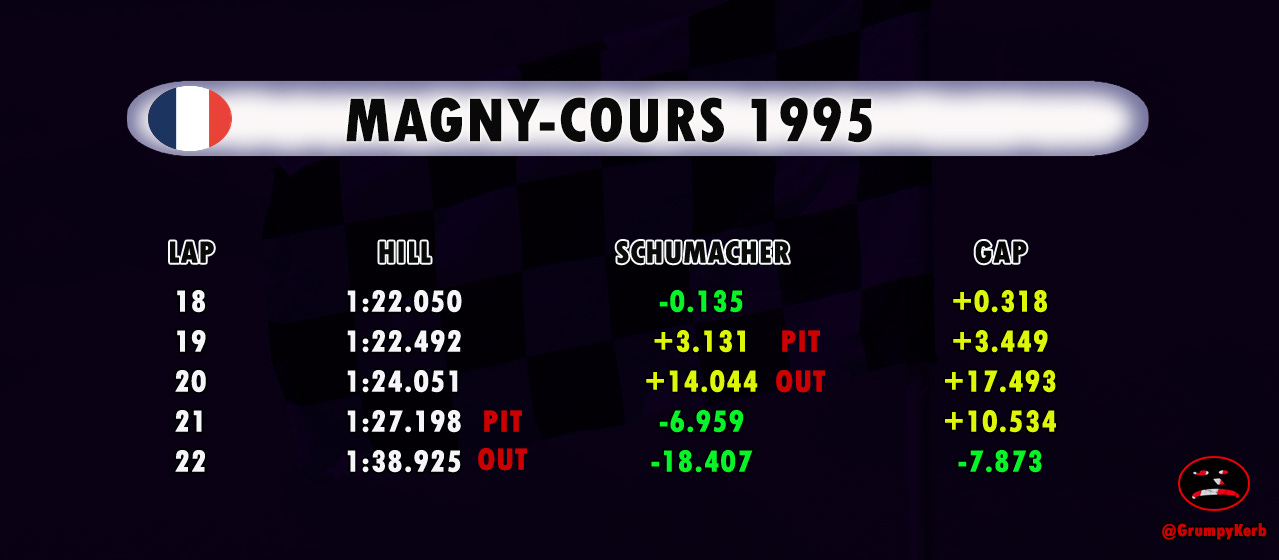

Hill led the race from pole position, closely pursued by charging Schumacher. The German was clearly faster and consistently filled the mirrors of the Williams, but he couldn't get close enough to make a move.

On lap 19, the leading duo encountered three backmarkers in close proximity. Benetton promptly called Schumacher into the pits, while Williams chose to keep their lead driver on the track.

The German emerged into clean air and set the fastest time on lap 21, the same lap his championship rival pitted after navigating through traffic for nearly two full tours.

After the out lap, Hill found himself 7.873 seconds behind Schumacher. He had previously led the German by 0.318 seconds before they encountered traffic.

Of course, Benetton had a faster car in France, and the team’s mechanics serviced their driver more quickly than their Williams counterparts. Still, the Grove team was outsmarted by Ross Brawn, the mastermind behind Benetton’s strategies.

Frankly, it was a frequent occurrence in 1995, just as it had been in the previous year. Brawn’s ability to think outside the box and adapt on the fly was like paper to Williams’ rock: often rigid and narrow-minded approach.

That’s not to say that Hill would have won the race, but to highlight how much more difficult his team made it for him.

The next race was, of course, the feral British Grand Prix, where desperation got the better of Hill, and he went for a move that barely had a chance to stick.

Not as Bad as It Looks

When the idea of writing this post first came to mind, I thought it would be quite challenging, akin to putting lipstick on a pig. To my surprise, after visually refreshing my memory and searching through the online archives of Motor Sport magazine, defending Hill’s tumultuous 1995 campaign turned out to be much easier than I had anticipated. The information I gathered did much of the work for me.

Of course, it is not my intention to absolve the Brit of his mistakes, such as the collision at Silverstone, the embarrassment at Spa, the crash at Nurburgring, and the beaching the car at Suzuka. That’s on him. The rest either had mitigating circumstances, could be attributed to mechanical failures, or were simply racing incidents. I don’t think the driver should bear the blame alone.

The criticism that Hill received for his performance in 1995 has been blown out of proportion, I would argue. At least half of it should be directed at the team. Williams failed their lead driver, both through mechanical failures and shortcomings in strategy, just as much as he failed them behind the wheel. Yet, strangely, their screw-ups have gone under the radar.